Extending Sub Rosa

Sub Rosa ( described in this paper ) is a system of quasiperiodic rhombic substitution tilings with $2n$-fold rotational symmetry, for any $n$. Sub Rosa takes care of the case of even symmetry, however it leaves open the case of odd symmetry. In this post, I describe a method for transforming a Sub Rosa tiling, reducing the rotational symmetry by a factor of $2$. This method only works for odd $n$, So this method and original Sub Rosa dovetail yielding a system of quasiperiodic rhombic substitution tilings with $n$-fold rotational symmetry for any $n$.

Terminology

As I said, the method is based on Sub Rosa, and several terms are both defined in Sub Rosa and used in the same sense in this post. Specifically the terms tiling, rhombus, substitution, uniformly recurrent, primitive, quasiperiodic.

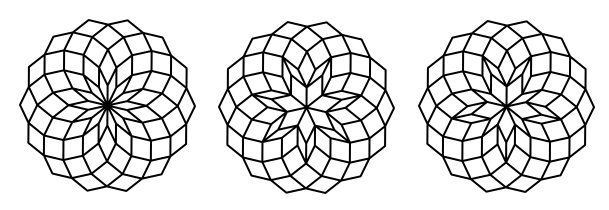

We refer to a broken rose as a rose with the inner-most two rows of petals reversed, as illustrated in the following diagram. As you can see, while a rose has $2n$-fold rotational symmetry, a broken rose has only $n$-fold rotational symmetry. We will also encounter random roses ( see diagram ) which have no rotational symmetry.

Roses: (from left) original, broken and random.

A cube is a patch of $3$ rhombuses, one $(2, n-2)$ rhombus and two $(1, n-1)$ rhombuses joined together to form a patch, which looks like a cube in perspective. To flip a cube means to rotate the patch by $180$ degrees about its center.

Theorem

The main result is the following theorem.

Theorem 1 For every $n\geq5$, there exists a quasiperiodic rhombic substitution tiling with $n$-fold rotational symmetry.

Method

There are two cases: if $n$ is even, we use an unmodified Sub Rosa tiling with order $\frac{n}{2}$. If $n$ is odd, we start with a Sub Rosa tiling of order $n$, and modify it as follows.

The initial tiling is a broken rose rather than the original rose that is used in Sub Rosa. For the substitution rules, flip “as many cubes as we can find” at the corner, edge or in the interior, wherever a rose or part-rose is found. There are two cases for the number of rhombuses found at a vertex - odd or even. In the even case we flip cubes that comprise all the rhombuses, and in the odd case there will be one rhombus left over. For symmetry, although it’s not strictly required, we always work counter-clockwise around a vertex.

Observations

The resulting tiling is uniformly recurrent. To prove this, consider a patch $P$ made from $n$ rhombuses of type $(2, n-2)$, joined together at their thin vertex. This patch $P$ appears at the center of the initial tiling. The patch $P$ will re-appear at the next level because at least one cube appears, and at the center of the cube there are three corners: two fat corners of $(1,n-1)$ rhombuses, each contributing $\frac{n-1}{2}$ cubes (since $n$ is odd, this is a whole number) and one thin corner of a $(2,n-2)$ rhombus, which contributes $1$ cube. Together these corners contribute $n$ cubes. Since all these cubes are flipped, patch $P$ appears at their center.

The resulting tiling exhibits $n$-fold symmetry, without exhibiting $2n$-fold symmetry. To prove this, observe that within all substitution rules, occurrences of roses or part-roses with $2n$-fold symmetry are flipped, causing the symmetry to deflate by a factor of $2$, giving rise to either a broken rose or a random rose.

Examples

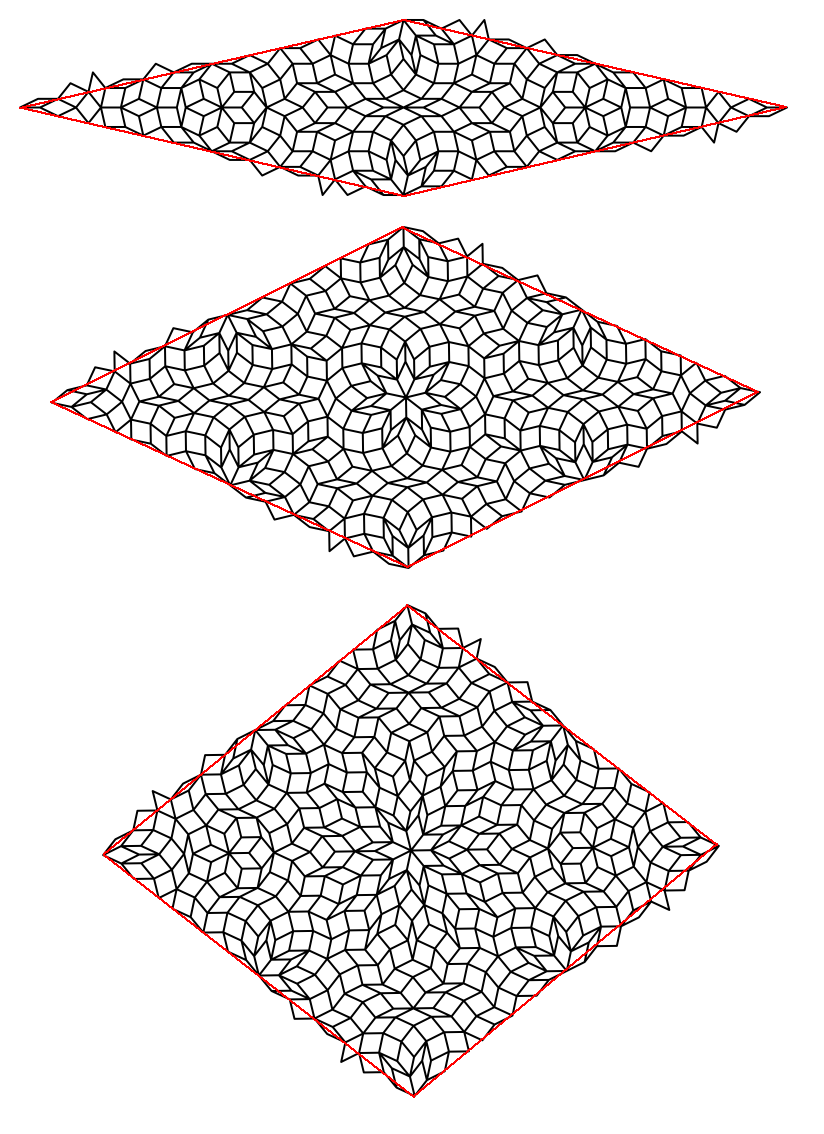

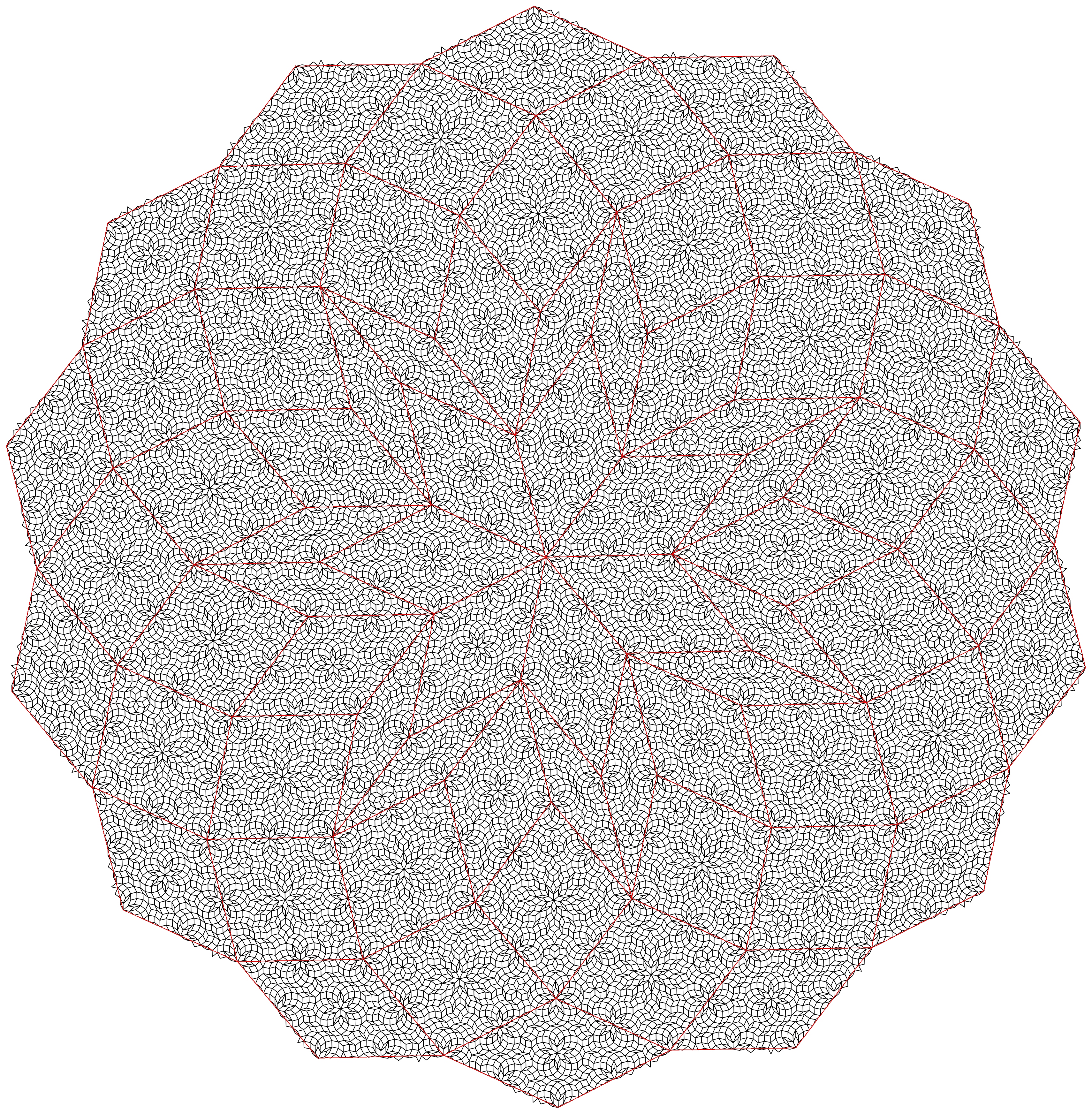

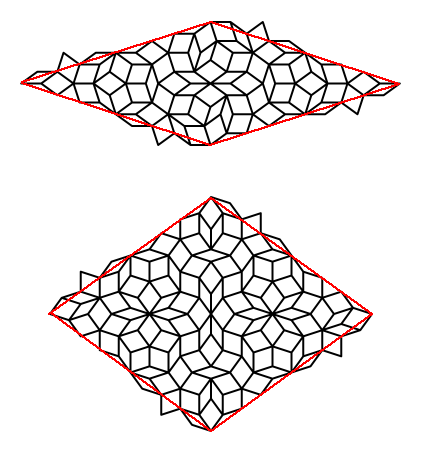

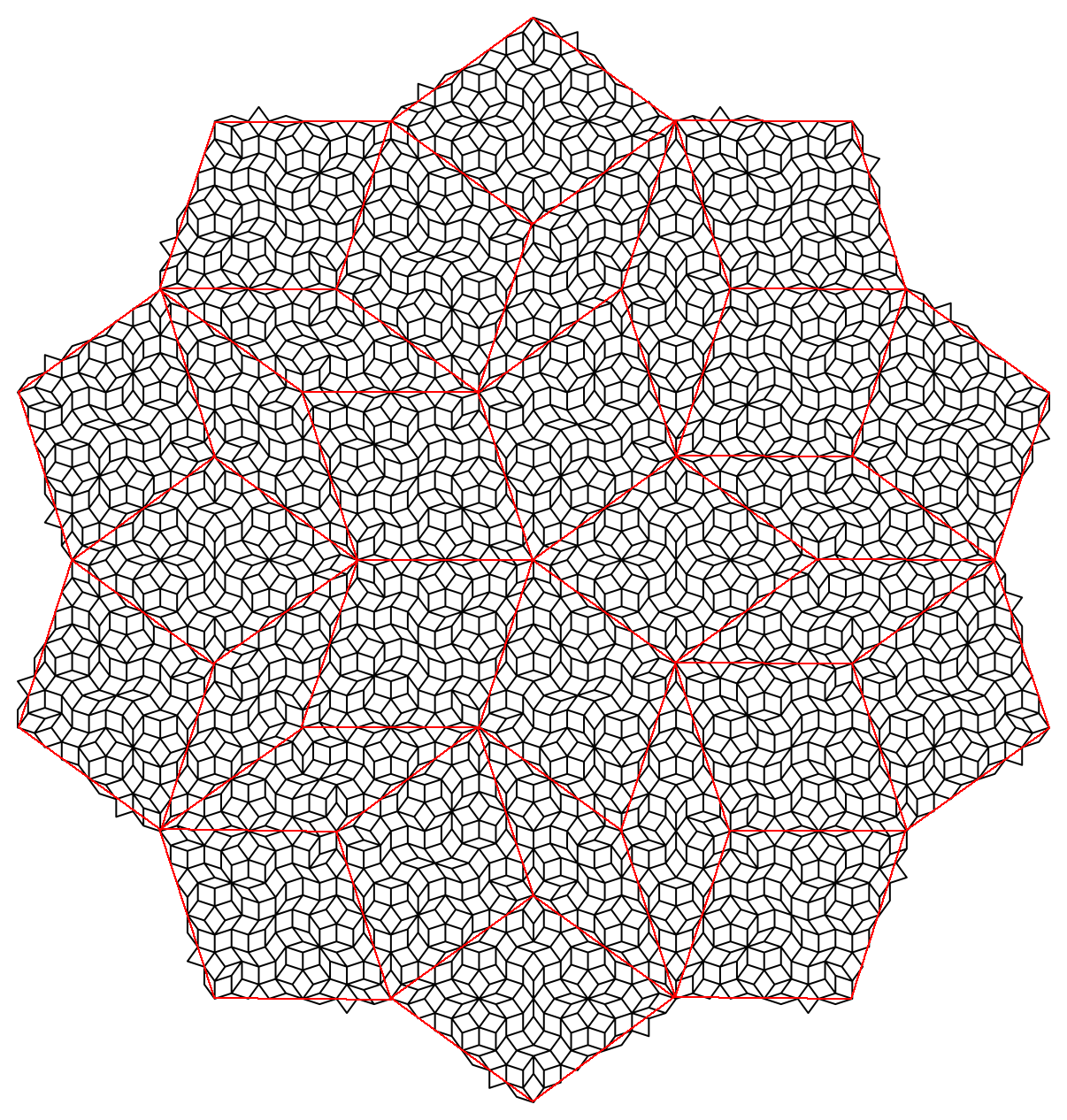

To illustrate the process, I present the modified substitution rules, and a tile patch for $n=5$ and $n=7$.

n=5

n=7